You might have heard the term COP26 quite a lot by now. Do you know what it’s all about? This our jargon busting guide to all things COP26.

What is COP26?

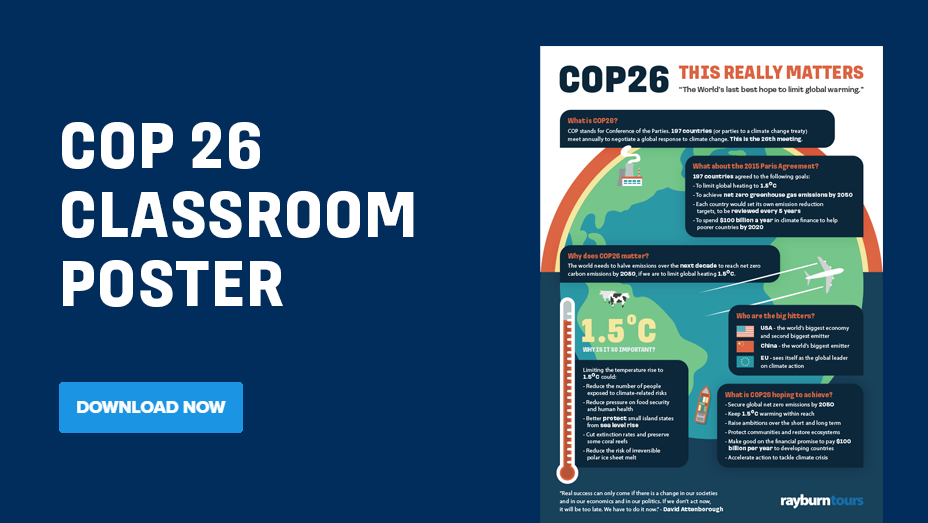

COP stands for Conference of the Parties. It is a summit of all the countries which are part of the United Nations’ climate change treaty. There are 197 members of this process and they are known as “parties” to the treaty. Since 1995 world governments have met nearly every year to negotiate a global response to climate change. This year is the 26th meeting.

It is to be hosted by the UK in Glasgow from 31st October to 12th November 2021. Governments and negotiators from 197 countries are expected to attend.

What about the Paris Agreement?

The historic Paris Agreement was reached in 2015 at COP21. Every nation pledged to work together to reduce greenhouse gases and limit global heating to well below 2°C above pre industrial levels, and aim for 1.5°C. Alongside this there was agreement to reduce the amount of harmful greenhouse gasses produced and to achieve net zero emissions in the second half of the century. Countries set their own targets to stay within those limits, in the form of nationally determined contributions (NDCs) and agreed to update their plan every 5 years. Finally there was an agreement to spend $100 billion a year in climate finance to help poorer countries by 2020.

Why does COP26 matter?

The commitments laid out in Paris did not come close to limiting global warming to 1.5°C. The science is clear: the world needs to halve emissions over the next decade and reach net zero carbon emissions by 2050, if we are to limit global temperature rises to 1.5 degrees by 2030. At COP26 governments are obliged to set out more ambitious goals for reducing emissions and must go further than they ever did to keep global temperature rises below 1.5°C.

Why is 1.5°C so important?

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) examined closely what a temperature rise would mean for the planet. They found a vast difference between the damage done by 1.5°C and 2°C of heating and concluded the lower temperature was much safer. If the world warms more than this threshold, millions more people in the most vulnerable communities around the globe will suffer from devastating droughts, storms, floods and other impacts of climate change.

Limiting temperature rise to 1.5°C could:

- Reduce the number of people exposed to climate-related risks by several hundred million.

- Reduce pressure on food security and human health.

- Better protect small island states from sea level rise.

- Cut extinction rates and preserve some coral reefs.

- Reduce the risk of irreversible polar ice sheet melt.

The IPCC concluded that there was still a chance for the world to stay within the 1.5°C threshold but that it would require concerted efforts. Crucially every fraction of a degree increase is important.

What about net zero?

To stay within 1.5°C, we must stop emitting carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases almost completely by 2050. There may be some residual emissions remaining, from processes that cannot be modified, but these must be offset by increasing the world’s carbon sinks, such as forests, peatlands and wetlands, which act as giant carbon stores. That balance is known as net zero.

To deliver on these targets countries will need to accelerate the phase out of coal, speed up the switch to electric vehicles, encourage investment in renewables and curtail deforestation.

Is COP26 just about 1.5°C?

Getting more countries to enhance their Nationally Determined Contributions and sign up to a long term net zero goal will be a central part of the negotiations but there will be focus on other important areas too.

- Climate Finance

This is the money provided to poor countries from public and private sources to help them cut emissions and cope with the impacts of climate change. Poor countries were promised that they would receive $100bn a year by 2020. That target has been missed. Developing countries will want reassurances that the money will be forthcoming as soon as possible and that a new financial settlement will vastly expand the funds available beyond 2025.

- Nature based solutions

Projects such as preserving and restoring existing forests, peatlands, wetlands and other natural carbon sinks and growing more trees will be important initiatives.

Who are the big hitters?

The USA is the world’s biggest economy and second biggest emitter. Now that Joe Biden has taken them back into the Paris Agreement their role in the negotiations will be pivotal.

China is the world’s biggest emitter but it’s still not clear whether China’s president Xi Jinping will come to Glasgow. China is yet to produce a new NDC, however, in a major step forward, last year, Xi committed China to peak emissions by 2030 and to reach net zero emissions by 2060. Whilst this is vital progress it’s not regarded as sufficient to keep the world at 1.5°C.

The European Union negotiates as a bloc at United Nations talks. It has embedded strong climate policies over the last two decades and sees itself as the global leader on climate action.

What are the sticking points?

Negotiations are likely to be far from straight forward. There are tensions between the USA and China over trade and national security but these two huge economies will need to find a way to work together if a successful outcome is to be achieved.

India has a rapidly growing economy and a high dependence on coal. It is believed that the Indian Prime Minister was close to committing to a net zero target but this was overtaken by the worsening Covid crisis. Will India take the significant step and embrace a net zero emissions target?

A recent Climate Council report has revealed that Australia is the worst climate performer of all developed countries. When you account for emissions produced in the country and those resulting from fossil fuel exports, Australia is the 5th biggest source of climate pollution worldwide, only behind the USA, EU, China and Russia. The country has so far refused to substantially strengthen its 2030 emissions reductions target and have continued to approve and fund new fossil fuel developments.

A recently leaked documents reveal that Saudi Arabia, Japan and Australia are among countries asking the UN to play down the need to move away from fossil fuels.

At an earlier climate summit, Brazil’s president promised to double the budget for protecting the Amazon, only to renege within days. The destruction of the Amazon, under his leadership, has brought the world’s biggest rainforest and huge carbon sink to the brink of becoming a source of carbon.

Then there’s the conundrum of carbon trading; a mechanism by which rich countries could hive off some of their carbon reduction to developing countries. It works on the basis that a tonne of carbon dioxide has the same impact on the atmosphere wherever it’s emitted. If it’s cheaper to cut a tonne of carbon dioxide in India rather than Italy, the Italian government could pay for projects in India that would reduce emissions there and count those “carbon credits” towards their own emissions cutting targets. However, the system has been open to abuse and there are questions regarding it’s adequacy in a world where all countries, developed or developing, need to cut emissions as soon as possible. In Madrid in 2019, the COP was derailed by arguments over the technicalities of carbon trading.

So what happens next?

In the words of David Attenborough

“Real success can only come if there is a change in our societies and in our economics and in our politics. If we don’t act now, it will be too late. We have to do it now.”

David Attenborough